Beginner's Guide to Working with Strings in Go

Learn the basics of the string data type in Go and avoid misunderstood mechanics: representation in memory, character encoding schemes, and more.

Regardless of your experience in computing, whether you're a beginner without a single written line of code or a senior developer with years of professional experience, strings and how they are represented is a commonly misunderstood concept.

This article assumes a basic familiarity with the Go type slice as well as basic programming knowledge.

This post intends to serve as a beginner's guide to working with strings in Go while also serving up some useful "gotchas" for those with a little more experience. Let's sling some strings.

How Does Go Define Strings?

In Go strings are represented in memory as an immutable (unable to be modified) sequence of bytes. Their general purpose being to process and represent text.

They can be initialized and printed like so:

var hello string = "Hello World!"

goodbye := "Goodbye!"

fmt.Println(hello, goodbye)

Output:

Hello World! Goodbye!

While the following definitions don't appear at face-value to be a slice of bytes, they're compiled as such. This behavior can be demonstrated with the lines treating the strings as slices. What happens when indexing strings like we would a slice?

greeting := "Greetings"

fmt.Println(greeting[2])

fmt.Println(greeting[4])

Output:

101

116

Wait, why are decimal numbers getting returned in the output? Like mentioned above, under the hood strings are a slice of bytes. The decimal numbers returned are the numeral representation of the characters we assigned in the string ("Greetings").

This shows that the results of the index printouts above appear to yield the ith character in the string (it actually turns out to be the ith byte... more on this below).

We must also be able to find the length of a string as well.

greeting := "Greetings"

lengthOfGreeting := len(greeting)

fmt.Printf("Length of greeting: %v", lengthOfGreeting)

Output:

Length of greeting: 9

Further, a length implies we can loop through the items held within the slice:

hello := "Hello World!"

for i := 0; i < len(hello); i++ {

fmt.Printf("%s ", hello[i])

}

Output:

72 101 108 108 111 32 87 111 114 108 100 33

The %s formatting verb prints the value passed to it in its default format (decimal value of the indexed byte in this case)

As expected, we get every byte composing the string returned.

To demonstrate the inherent immutability of strings, let's try to modify a string:

immutableString := "I can't be modified"

immutableString[5] = 'B' // ILLEGAL

This is illegal behavior, however concatenation is supported for combining strings:

immutableString1 := "I can't be modified"

immutableString2 := " but I can be combined with another"

fmt.Println(immutableString1 + immutableString2)

Output:

I can't be modified but I can be combined with another

Strings can also be sliced to grab a substring:

stringToSlice := "You can grab just a sliver of this string"

substring := stringToSlice[12:25]

fmt.Println(substring)

Output:

just a sliver

Behind the scenes when slicing a string, the Go compiler will create a new slice that is composed of the same bytes that start at the beginning index (12) and end at the closing index (25). Either or both indexes can be omitted as well:

stringToSlice := "You can grab just a sliver of this string"

substringBeginning := stringToSlice[:8]

substringEnding := stringToSlice[30:]

fullSliceCopy := stringToSlice[:]

fmt.Println(substringBeginning)

fmt.Println(substringEnding)

fmt.Println(fullSliceCopy)

Output:

You can

this string

You can grab just a sliver of this string

When formatting output you can also use escape sequences to modify your output. This is how to use both \t (tab escape) and \n (newline) in some sample code:

inventory := "ID:\tCost:\n55\t$39.99\n56\t$10.99\n"

fmt.Println(inventory)

Output:

ID: Cost:

55 $39.99

56 $10.99

Using these formatters is nifty for achieving some nicely aligned and spaced output. But what if we wanted our string to be interpreted literally, where each escape was no longer used as such.

For this we can use a raw string literal.

In Go these are represented using backquotes (``). Let's use the same string above to see the difference in output:

inventory := `ID:\tCost:\n55\t$39.99\n56\t$10.99\n`

fmt.Println(inventory)

Output:

ID:\tCost:\n55\t$39.99\n56\t$10.99\n

The backslashes that were used as escapes in the string literal are interpreted literally in a raw string literal.

Big Characters

Let's backup now and look at another example that can stump the uninitiated. Try to guess the length of the string below:

greek := "I'm in ΔΔΔ"

lengthOfGreek := len(greek)

fmt.Println(lengthOfGreek)

Result:

13

Hold up, if there are 10 characters (including spaces) in the string then why is 13 returned as the result? Because the last 3 characters (Greek Capital Delta's) in the string are represented using more than a single byte each.

This can be further shown by looping through the string like we did before, a byte-at-a-time:

greek := "I'm in ΔΔΔ"

for i := 0; i < len(greek); i++ {

fmt.Printf("%x ", greek[i])

}

Output:

73 39 109 32 105 110 32 206 148 206 148 206 148

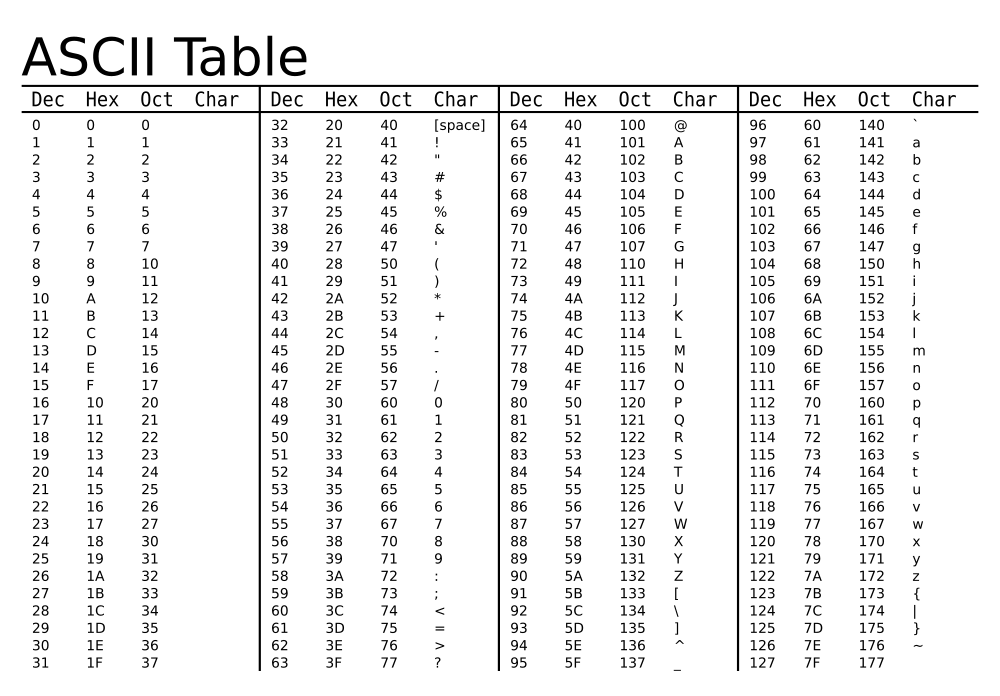

This prints out all 13 bytes that make up the string in their hexadecimal representation (with the %x format verb). If your first though is "Why can't characters be represented with a single byte?", you're not crazy.

Enter Unicode

What is Unicode?

Unicode is a global standard, mapping characters with identifiers called code points. The purpose of this standard is to capture characters from all written languages worldwide and define exactly how they can be represented as bytes. This enables consistency with the international computing community. When everyone can agree on what byte sequence displays θ (greek small letter theta / byte sequence 0x03B8) it makes it easy to tailor you application to support whatever written language is desired.

These code points are represented in hexadecimal notation. Here are some sample characters and their corresponding code points:

- 'a' -> U+0061

- 'A' -> U+0041

- 'Σ' -> U+03A3

Naturally in order to represent this many characters, more than one byte (8 bits) is needed. In the olden days, ASCII was king and served as the only character set worth worrying about. It allowed you to represent all English lower-case and upper-case character, numbers, punctuation, and some control device-control characters within a single byte (more precisely 7 bits = 27 = 128 characters).

This was great if you were an English speaker. But with the rise of the internet, communication lines spread across the globe and along with it arose the complexities of representing international languages in code. Unicode was eventually adopted as the golden standard to adhere to when representing characters in other languages.

For a historical look at this topic, check out Joel Spolsky's seminal article about character encodings

While there are several schemes of translating Unicode to bytes, the most widely accepted one is UTF-8.

What is UTF-8

UTF-8 is a character encoding scheme that maps Unicode code points to sequences of bytes. Each Unicode character is represented in variable-length fashion. Each character uses anywhere from 1-4 bytes in memory.

This is why calling len() on a string can sometimes yield a length larger than the number of characters within that string. Many Unicode characters require more space than a single byte.

In Go, strings are interpreted as UTF-8 by default.

A nifty way Go seeks to make working with strings more convenient is through the type rune.

Runes

rune is an alias for int32 (4 bytes worth of space) and helps when processing strings. Go supports a cleaner alternative to the direct indexing loop shown above.

This loop iterates over a string a rune-at-a-time (character-at-a-time instead of byte-at-a-time):

thetas := "thetas: θθθ"

fmt.Printf("i\tr\n")

for i, r := range thetas {

fmt.Printf("%d\t%q\n", i, r)

}

Output:

i r

0 't'

1 'h'

2 'e'

3 't'

4 'a'

5 's'

6 ':'

7 ' '

8 'θ'

10 'θ'

12 'θ'

As shown in the output above, the last 3 characters take up 2 bytes each.

The %q format verb outputs the given value while escaping any non-printable characters (invalid UTF-8 byte sequence)

Adding the range loop to your repertoire makes rooting out issues in strings much simpler.

You can also define rune literals to represent a single rune using single quotes (' '):

runeLiteral := 'θ'

fmt.Println(runeLiteral)

fmt.Printf("%q\n", runeLiteral)

Output:

952

'θ'

We've already mentioned that strings are technically a slice of bytes. It follows that we can convert to and from this type:

country := "France"

countryBytes := []byte(country)

fmt.Println(country)

fmt.Println(countryBytes)

Output:

France

[70 114 97 110 99 101]

On top of the built-in support for processing runes, more string processing power is provided by Go's unicode package.

FIN

After this read you should have all the tools to slice-and-dice strings in Go and not be surprised by the curveballs they can throw the budding programmer.

Cheers! 🍺

For a more advanced read on Go string intricacies, this Rob Pike Go blog post is a must read